The Stethoscope and How To Use It

Posted By: Kubin | Stethoscopes

The stethoscope.

It’s practically the symbol of physicians and physician assistants. Most of us know the basics: you put the things in your ears, the other end on a sick person, and listen. But stethoscopes can do much more. The following are a few facts about the tool, followed by a more complete list of its uses. If you’re new to the medical field, getting comfortable with your stethoscope will make you a better student and clinician of medicine.

Origin. Early stethoscopes were little more than “ear tubes,” that were invented in 1816 by René Laennec at the Necker-Enfants Malades Hospital in Paris, France. They were updated here and there, but current designs are credited to Dr. David Littman of Harvard University who made them lighter and gave them better acoustics.

Auscultation: the act of listening for sounds within the body. Latin auscultation-, auscultatio, act of listening, from auscultare to listen.

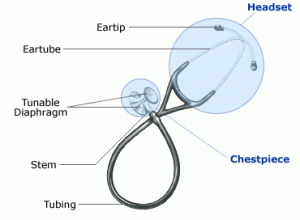

Parts. Even modern scopes are fairly simple (except the electronic ones that digitally amplify sound). The following diagram will provide you with the important vocabulary:

The most important parts to know are the diaphragm, which is larger, flatter side of the chest piece, and the bell, which has the smaller, concave piece with a hole in it. Switch between the two by twisting the chest piece 180 degrees. You’ll hear a click. Then tap each side to see which one is “on.”

How it works. The diaphragm is a sealed membrane that vibrates, much like your own eardrum. When it does, it moves the column of air inside the stethoscope tube up and down, which in turn moves air in and out of your ear canal, and voila, you hear sound. Since the surface area of the diaphragm is much greater than that of the column of air that it moves in the tube, the air in the tube must travel more than the diaphragm, causing a magnification of the pressure waves that leave the ear tip. In your ear, larger pressure waves make louder sounds. This is how stethoscopes amplify sounds.

How to wear it. Place the ear tips in the ears, and twist them until they point slightly forward (toward your nose). If you do it right, you’ll make a good seal, and sounds in the room will become very faint.

Holding it. The important tip here is that in most cases you’ll want to hold the chest piece between the distal part of your index and middle finger on you dominant hand. This grip is better than using your fingertips around the edge of the diaphragm/bell because it allows you to press against the patient without your fingers rubbing it and creating extra noise. A gentle touch is best.

Placing it. Place the chest piece (diaphragm or bell) directly against skin for the best sound transmission. If you’re in a hurry you can hold it over one thing layer of clothing, such as a T-shirt, but this isn’t recommended, as doing so risks missing nuances that might be crucial.

What you can do with it: If you learn the following, you’ll be using yours more than 90% of clinicians. The links will take you to free pages on the specific technique.

- Measuring blood pressure. Probably the most common use, but often done poorly. Placement of the blood pressure cuff is critical. Also, many students are taught that the diastolic BP (e.g. 120/80) is the point in which they can no longer hear the thump of the brachial artery. More accurately, diastolic BP is the number at which the volume of the thump drops dramatically. This is often 4-10 mm Hg higher than when the sound disappears completely.

- Assessing lung sounds: allows you to identify the rate, rhythm and quality of breathing, any obstructions of the airways, as well as rubs that indicate inflammation of the pleura. Don’t forget to start above the clavicle, since lung tissue extends that high. Also, when you listen to the back, have the patient lean forward slightly to expose the triangle of auscultation. Remember that for lung sounds (according to the Bates “Bible,”) we listen in six paired areas on the chest, and seven paired areas on the back. I remember this with the mnemonic “6AM – 7PM,” (6 anterior pairs, and 7 posterior pairs). Always listen to left and right sides at the same level before moving down to the next level – this way you get a side-by-side comparison, and any differences will be more apparent.

- Assessing heart sounds. We listen for rate, type, and rhythm of heart sound, as well as any sounds that shouldn’t be there (adventitious sounds), such as gallops, murmurs or clicks. All hearts sound the same at first. But after listening to many hearts, eventually sounds will seem to jump out at you. For heart sounds, we listen to the four primary areas: left and right of the sternum at the level of the 2nd rib, left of the sternum at the 4th rib, and on the left nipple line at the level of the 5th rib. Remember these with the mnemonic “2-2-4-5.” The names of the valves that you are hearing in these locations are: (2 right) aortic, (2 left) pulmonic, (4) tricuspid, (5) mitral. Remember these with the mnemonic “All Patients Take Meds.” Some of my friends use the mnemonic Apartment M2245 (APT M2245).

- Assessing Bowel Sounds. This is easy to do, and important if there may be a bowel obstruction or paralytic ileus. The gurgling, bubbling noises are called borborygmi. Go figure.

- Detecting bruits. A bruit (pronounced “broo’-ee,”) is an abnormal whooshing sound of blood through an artery that usually indicates that the artery has been narrowed, causing a turbulent flow, as in arterioscleroisis. Bruits are abnormal – if the patient is healthy and “normal,” you should not hear any bruits. Bruits can be detected in the neck (carotid bruits), umbilicus (abdominal aortic bruits), kidneys (renal bruits), femoral, iliac, and temporal arteries. The first true bruit I ever heard was umbilical, just above a patient’s belly button, and when I heard it I knew immediately that the patient had an abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA). It was an exciting find for me, and it might have saved my patient’s life.

- Measuring the span of the liver. Usually this is done with percussion (tapping the belly), but another neat way is to place the stethoscope below the right nipple, the other index finger just above the belt line in line with the nipple, and gently scratch the skin up toward the chest piece of the stethoscope. When you are over the liver, the sound will become more dull. Marking the location where the dullness begins and ends provides a decent measurement of the liver size in that location. About 10 cm is normal at the nipple line.

- Hearing Aid. Finally, the stethoscope makes a nice hearing aid with hearing impaired patients. Put the eartips in the patient’s ears, and talk into the chest piece. Handy in the ER!

Diaphragm vs. Bell. The diaphragm is best for higher pitched sounds, like breath sounds and normal heart sounds. The bell is best for detecting lower pitch sounds, like some heart murmurs, and some bowel sounds. It is used for the detection of bruits, and for heart sounds (for a cardiac exam, you should listen with the diaphragm, and repeat with the bell). If you use the bell, hold it to the patient’s skin gently for the lowest sounds, and more firmly for the higher ones.

Which one should I buy? Plan on spending no less than $60 for a quality stethoscope. Cheaper ones can work alright, but aren’t as durable, and have weaker sound profiles. The standard by which all others are measured is generally accepted to be the 3M Littman Cardiology III. Don’t spend gobs of money on a digital unless you know you will be working in cardiology – and maybe not even then. To see our stethoscope recommendations, visit stethoscope buyer’s guide page.

Infection control. Clean your stethoscope regularly, particularly the chest piece. Studies have found that stethoscopes are frequently the vectors for patient-to-patient disease transmission. Just wipe the chest piece with an alcohol prep pad to disinfect.

19 comments

Leave a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

How do I know what type of illness a person has by listening to their heartbeat?

Some illnesses have characteristic sounds. Atrial fibrillation has an “irregularly irregular” rhythm, and the characteristic whooshing sound of mitral regurgitation between the first and second heart sound makes it fairly easy to identify, once you’ve heard it a few times. Carotid bruits (rushing sounds of blood on the neck) indicate a carotid atherosclerotic plaque. Also pulmonary illnesses can sometimes be diagnosed solely on their sound (the whistling sound of asthma and the “crackling” sounds of pneumonia. Stethoscopes are powerful tools when used by well-trained clinicians.

To learn about these, you should check out the terrific site, The Auscultation Assistant.

Wow! This is informative (Sorry, being Captain Obvious here). I plan on getting a Littmann Classic II SE. Think that’s good?

A comprehensive guide to using a stethoscope, with hundreds of audio recordings can be found at http://www.practicalclinicalskills.com

Can you buy a stethoscope even if you’re not a doctor?

Yes – anyone can buy a stethoscope.

Thanks. I am a FNP student and just bought the Bates’ pocket guide.

How valid are stethoscopic auscultations when the patient is still

wearing his clothing ? A GP listened to my chest through my thermal

vest, would that be an acceptable way of listening to a person’s chest?

Malcolm – the most accurate sounds come from listening directly on the skin. But it depends what you’re looking for and to some extent how experienced you are. Certain clothing, like sweaters and silk are nearly impossible to listen through, even for low frequency sounds, like heart tones. For a physical exam on a patient without complaints, listening through one layer (say a soft cotton shirt) is usually not a problem for an experienced clinician. But if you’re looking for something with fairly subtle sounds, such as the “crackle” sound pf rales, you need to be on skin.

Summary:

-through skin is best, but in most cases an experienced clinician will have no trouble with one layer of soft/smooth clothing

Hi Paul, Thanks for your comments.

The GP in question was a GP Registrar just 5 months into her

GP training. She seemed to be nervous in using her stethoscope,

putting it to the upper left lung once and then upper right once

and saying that she could hear nothing abnormal. I am a 67 year old

male and every other GP who I have ever encountered has asked

me if I had ever had major lung surgery, as previous auscultation

has shown up anomalies due to a thoracotomy in my 20’s and they commented on thickening and a less effective result on one lung.

I do not wish to be contentious or get a young doctor into trouble but I know I have my annual bronchitis and she say’s there is

nothing there.

Thanks for your help.

Malcolm, UK.

Great article on stethoscopes. I’m researching them right now to buy one just for home use, I’m not a medical student or professional but like to be health conscious. At least I’m trying to be more health conscious. Thanks particularly for the section about how to actually use a stethoscope for a handful of common reasons, very helpful!

Thanks, Richard. Stethoscopes are fun to use and not so hard, once you’ve spent a little time with them. Medicine doesn’t need to be mysterious!

Thanks Paul. I’m a new paramedic and I thought that a good stethoscope was a great way to start my field of training. I purchased a Littmann cardiology III. First thing I did was have it monogrammed. Now that I’ve got it back, it’s time to learn just how much pressure is needed to hear certain things like heart tones or lung sounds. When to use the bell vs. diaphragm.

Go get ’em Margaret!

Good read. I picked up a new skill, in using it as a makeshift hearing aid.

This was very helpful. Just got a Littman as a gift. It’s so much better than what I was using, and now I’ve learned some new skills from your article.

Thanks

How can I store a stethoscope?

Stethoscopes are easy to store. They’re very durable. About the only thing you want to avoid if you’re not going to be using it for a long time is heat and direct sunlight. The polyurethane tubing will dry out and crack if it sits in the sun / by a radiator / in the trunk of a hot car for too long. I suggest you but it in a ziplock back and keep it somewhere away from heat and sunlight. Or hanging from a coathook in a closet is usually fine too. But again, good stethoscopes (I use the Littman Cardiology III) are VERY durable.